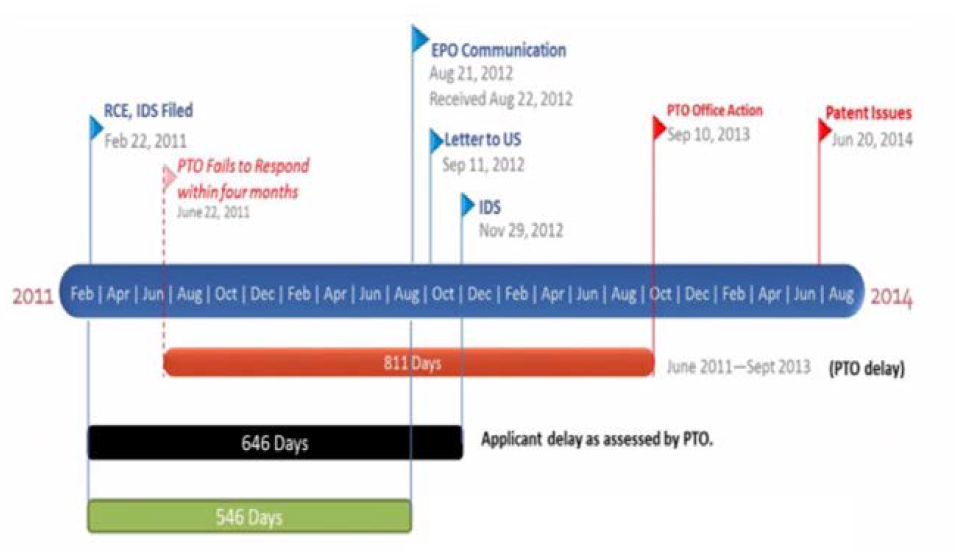

It is important to thoroughly review the Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) calculation when your U.S. patent issues. This was illustrated in the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals decision yesterday in Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Andrei Iancu (January 23, 2019). Patent Term Adjustment (“PTA”) The term of a patent is 20 years from the earliest U.S. filing date. Because the term includes the period during which the application is pending before the PTO, the Patent Office has the authority to adjust the term of a patent by adding days to account for prosecution delays caused by the Office. Such adjustments are favorable to the patentee because they extend the life of the patent. Correspondingly, the PTO can reduce the PTA in order to account for delays caused by the applicant. Before delving into the details, the basic gist of the Supernus case involved a supplemental filing by a patent applicant, and the impact that filing had on the PTA when the patent ultimately issued. The supplemental filing was made to disclose information from a foreign counterpart application. By its nature, this information was unknown to the patent applicant (and indeed did not even exist) for a significant amount of time during pendency of the U.S. application. When calculating “applicant delays” to reduce PTA for the U.S. patent, the PTO counted the time from the date an RCE was filed by the applicant (which preceded the foreign action by 546 days), to the date the patent applicant disclosed it to the USPTO. This case discusses some fundamental questions relating to PTA: what counts as delay on the part of applicant, and how does the PTO calculate that delay? For each patent, the PTA determination is stated on the Issue Notification Letter. It is important to review that determination, and raise any objections, promptly. Supernus v. Iancu The case involved U.S. Patent No. 8,747,897, titled “Osmotic Drug Delivery System.” Supernus filed the application on April 27, 2006, followed by lengthy prosecution that included an RCE filed in February 2011, and ended with the ‘897 patent issuing on June 10, 2014. As is often the case, Supernus had a parallel European patent application pending. In that European case, a third party filed a Notice of Opposition on August 21, 2012. European counsel notified Supernus of the Opposition 21 days later, on September 11, 2012. On November 29, Supernus filed a supplemental Information Disclosure to disclose the Opposition and cited references to the USPTO. Relevant dates are shown here: In calculating term adjustment for the patent, the PTO reduced the PTA by 886 days for applicant delay. Supernus objected to 646 days that were assessed for the period between the February 22, 2011 RCE filing and the November 29, 2012 submission of the supplemental IDS. Thus, the entire period between the filing of the RCE and the supplemental IDS was counted as “applicant delay” against the PTA for this patent, despite the fact that the opposition did not even exist until August 2012. Supernus filed a request for reconsideration of the PTA, which the USPTO rejected. Supernus then appealed to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, which ruled in favor of the PTO. The case was then appealed to the Federal Circuit. Supernus argued, and the PTO did not dispute, that Supernus could not have undertaken any efforts to conclude prosecution of the patent application during the 546-day period between the filing of the RCE on February 22, 2011, and the EPO’s notification of the European Opposition on August 21, 2012. The Federal Circuit stated the precise question before it was “whether the USPTO may reduce PTA by a period that exceeds the ‘time during which the applicant failed to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution.’” The Federal Circuit reversed the district court and agreed with Supernus. The Federal Circuit held: “On the basis of the plain language of the statute, we hold that the USPTO may not count as applicant delay a period of time during which there was no action that the applicant could take to conclude prosecution of the patent. Doing so would exceed the time during which the applicant failed to engage in reasonable efforts.” The Federal Circuit found the PTA statute imposed two limitations on the amount of time that the USPTO can use as “applicant delay” for purposes of reducing PTA:

Thus, the statutory period of PTA reduction must be the same number of days as the period from the beginning to the end of the applicant’s failure to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution. In the Supernus case, there was no action Supernus could have taken to advance prosecution of the patent during the 546-day period, particularly because the EPO notice of opposition did not yet exist. When reviewing PTA for your patent, it is important to confirm any reduction to the PTA is in fact equal to any period of time in which applicant has failed to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution. Particularly when your application involves foreign counterparts, any reduction should correlate to the specific time period during which applicant failed to engage in reasonable efforts to prosecute the application. Finally, although this case involved post-RCE filings, the principles of this case can apply to any supplemental IDS.

0 Comments

Yesterday, the Supreme Court unanimously held that an inventor’s sale of an invention to a third party who is required to keep the invention confidential may place that invention “on sale” under U.S. patent law, thus precluding patent protection of that invention. Helsinn HealthCare S.A. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., 568 U.S. (2019). The case involved Helsinn Healthcare S.A., a Swiss pharmaceutical company that produces Aloxi, a drug that treats chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Helsinn entered into two agreements with MGI Pharma, Inc., a Minnesota pharmaceutical company that markets and distributes drugs in the U.S. The two agreements, executed in April 2001, included a license agreement and a supply and purchase agreement. Both agreements required MGI to keep confidential any proprietary information received under the agreements. Of note, the existence of the agreements was publicly disclosed, both through press releases and in SEC filings. However, the specific dosage formulations covered by the agreements was not publicly disclosed. Nearly two years after signing these agreements with MGI, Helsinn filed a provisional patent application covering the active ingredient in Aloxi. Helsinn subsequently filed other patent applications that claimed priority to the 2003 provisional. The case turned on the question of whether, under the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA), an inventor’s sale of an invention to a third party who is obligated to keep the invention confidential qualifies as prior art for purposes of determining patentability of the invention. The Supreme Court unequivocally answered “yes.” The text of the opinion is relatively short. In authoring the opinion, Justice Thomas first noted that every patent statute since 1836 has included an on-sale bar. Justice Thomas then turned to Supreme Court precedent and acknowledged the specific issue had not been addressed: “Although this Court has never addressed the precise question presented in this case, our precedents suggest that a sale or offer of sale need not make an invention available to the public.” Justice Thomas looked to Federal Circuit precedent as explicitly recognizing this implicit thread running through Supreme Court jurisprudence: "The Federal Circuit – which has ‘exclusive jurisdiction’ over patent appeals … has made explicit what was implicit in our precedents. It has long held that ‘secret sales’ can invalidate a patent.” Interestingly, the two Federal Circuit cases cited here go further than the Helsinn fact pattern, in that they involve sales that were kept completely secret. After reviewing statutory language and case law, Justice Thomas concluded that Congress did not alter the meaning of “on sale” when it enacted the AIA. Thus, in the Court’s view, this decision is merely following the law as it stands. Pharmaceutical and biotech companies often face this scenario, where they seek business partnerships to formulate, run clinical trials, and/or produce their products. In light of this decision, it remains critically important that patent applications be filed before such license and/or supply purchase agreements are executed. |

AuthorKarrie Weaver practices intellectual property, trademark, patent, and trade secret law. Archives

February 2021

Categories |

612.386.0565

Copyright 2021. Weaver Legal and Consulting LLC. | All rights reserved.

Website by RyTech, LLC

Copyright 2021. Weaver Legal and Consulting LLC. | All rights reserved.

Website by RyTech, LLC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed