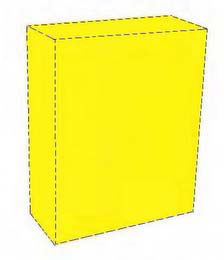

Recent efforts by General Mills to assert rights in the color yellow in connection with its CHEERIOS® breakfast cereal boxes have brought the issue of how color can function as a trademark into focus once again. Since at least as early as the 1980’s, U.S. trademark law has recognized that color can function as a trademark and is thus eligible for trademark protection. In its 1995 Qualitex decision, the Supreme Court definitively agreed, concluding that “sometimes, a color will meet ordinary legal trademark requirements. And, when it does so, no special legal rule prevents color alone from serving as a trademark.” As with all legal statements, the key is in the word “sometimes.” How Can Color Become a Trademark? Acquiring trademark rights in a color is not an easy task. A company must show that the color has become distinctive of its goods in commerce, and that the color does not serve any other significant function. Here are some well-known examples of companies who have successfully established trademark rights in a color: Owens-Corning Pink, Qualitex green-gold, Tiffany Blue, Barbie Pink, Wiffle Ball Bat Yellow, UPS Brown, 3M Canary Yellow, Target Red, Coca Cola Red, Christian Louboutin (red outsoles on shoes), and The Home Depot Orange. For a color to function as a trademark, customers must come to treat a particular color on a product or its packaging as signifying a brand. Taking Owens-Corning Pink as an example, the pink coloring of its insulating material seems unusual in context, and the particular hue has no other significant function. That color has come to identify and distinguish the insulation products – to indicate their source. In this instance, the color has acquired “secondary meaning,” where, in the minds of the public, the primary significance of the color is to identify the source of the product rather than the product itself. Limits to Color as a Trademark Against this backdrop, General Mills recently attempted to register the color yellow on packages of “toroidal” (ring or doughnut-shaped) oat-based breakfast cereal, the company’s CHEERIOS® cereal. The trademark application looked like this: General Mills described their trademark as consisting “of the color yellow appearing as the predominant uniform background color on product packaging for the goods. The dotted outline of the packaging shows the position of the mark and is not claimed as part of the mark.” The U.S. Trademark Office refused the trademark application, and General Mills appealed to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB). The TTAB agreed with the USPTO and rejected General Mills’ bid to register yellow for its CHEERIOS® cereal. In deciding the case, the Board conceded that “by their nature color marks carry a difficult burden in demonstrating distinctiveness and trademark character.” The record showed that General Mills had begun using the color yellow on its CHEERIOS® cereal boxes at least as early as 1944. The company introduced evidence that it had expended over $1 billion in marketing in a single decade, and that sales of CHEERIOS® cereal exceeded $4 billion in that same period (1995 to 2015). In looking at General Mills’ trademark application, the Board was influenced by the existence of several other companies who use yellow colored cereal packaging (boxes and bags) for similarly-shaped, oat-based cereals, including some of General Mills’ competitors. The Board concluded, “The presence of products of this type in the marketplace interferes with the development among relevant customers of a perception that the color yellow on packaging indicates that Applicant is the source of the goods (or that there is any single source of such goods)." Think about the cereal aisle in your local grocery store. When you turn down this aisle, you are often confronted with a rainbow of brightly colored packaging, for a large number of different cereals. Several of these boxes are yellow. The Board found that customers are accustomed to seeing numerous brands from different sources offered in yellow packaging and are likely to view yellow packaging simply as eye-catching ornamentation customarily used for the packaging of breakfast cereals generally. The Board also looked at the industry practice of ornamenting breakfast cereal boxes with bold graphic designs and prominent word marks (in addition to bright background colors). Looking at General Mills’ cereal packaging generally, the Board found that customers do not perceive the color yellow alone indicate the source of General Mills’ breakfast cereal. The CHEERIOS® “yellow box” case demonstrates the difficulties in protecting trademark rights in a color per se. This case presents a refinement in color trademark law, as well as guidance for companies interested in non-traditional trademark protection for their valuable brands.

0 Comments

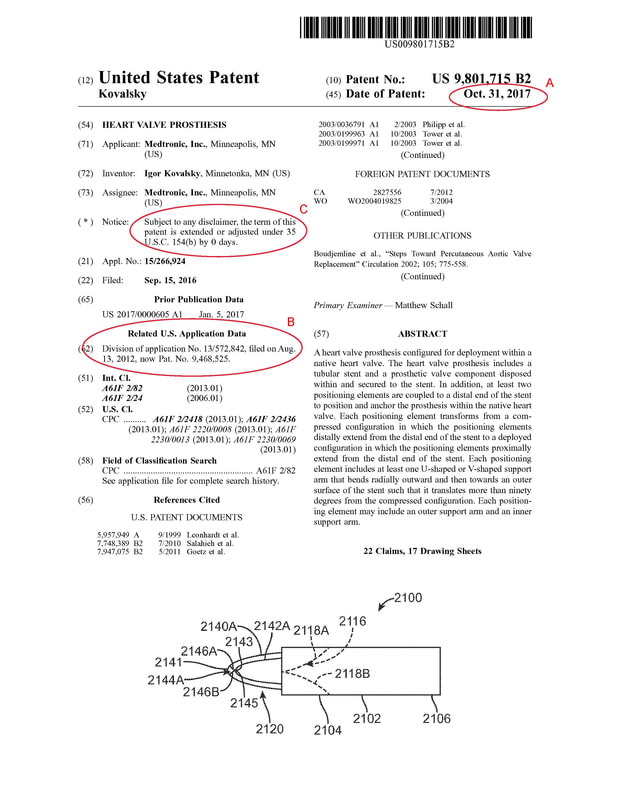

A patent is issued in the name of the United States under the seal of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). A patent confers “the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United States or importing the invention into the United States” and its territories and possessions for a period of time. So, how long does a patent last? On the date a patent issues, the “right to exclude” comes into force. So, how long can a patent owner exclude others from the above activities, or in patent parlance, what is the “patent term?” To determine the “life” of a patent, you must start with the earliest filing date of the patent application in the United States. Generally speaking, a patent term is 20 years from that date. In order to keep that patent in force, the patent owner must pay maintenance fees at three specific time periods during the patent term. Four important aspects of a patent term thus include: (1) what is the issue date of the patent, (2) when was the application first filed in the US, (3) has the USPTO adjusted the patent term, and (4) when are maintenance fees due? It is best to consult a patent attorney or agent to determine the actual expiration date of a patent, but you can begin to calculate the expiration date by looking at the front page of the patent of interest. For example, in the patent below, you can see (A) the issue date of the patent (the date from which the patent is in force), (B) the earliest date the application was filed in the United States, and (C) the patent term adjustment: In this Example, the patent rights are in force on October 31, 2017 (A). It was first filed in the United States on August 13, 2012 (B), and it did not receive any patent term adjustment (C). Now to the calculation: 20 years from (B) is August 13, 2032 + zero (0) days of patent term adjustment = an expiration date of August 13, 2032. The patent owner can enforce the patent for the period of October 31, 2017 to August 13, 2032, so long as they pay maintenance fees. Although it is best to verify items (B) and (C) through the USPTO Patent Application Information Retrieval (PAIR) system, this can give you a starting place for determining the patent term. You can access Public PAIR here: https://portal.uspto.gov/pair/PublicPair Maintaining the Patent Once the patent is issued, it must be maintained by paying maintenance fees to the USPTO. The USPTO established three 6-month time periods during the patent term when maintenance fees are due: (1) at 3 to 3.5 years; (2) at 7 to 7.5 years; and (3) at 11 to 11.5 years. These dates are measured from the Date of Patent, (A) in the example above. If a maintenance fee is not paid by the due date, there is a grace period of 6 additional months after the deadline, during which the fee can be paid (with a surcharge). Information about paying maintenance fees can be found at: https://www.uspto.gov/patents-maintaining-patent/maintain-your-patent. To see specific maintenance fee deadlines and whether a patent owner has paid them, select “View maintenance fee information” from this webpage. After a patent expires, either by running through its 20-year term, or because the patent owner failed to pay a maintenance fee, the public is free to use the invention claimed in that patent. Note, however, that this right is subject to any other patents that may exist in the particular field. Patent terms are as individual as the technology they describe. Although this article provides some guidelines for understanding how long a patent can be enforced, additional technical considerations such as terminal disclaimers, have not been covered. It is best to consult with a patent attorney or agent to determine the specific patent term and implications of a specific patent. Questions? Feel free to contact me. |

AuthorKarrie Weaver practices intellectual property, trademark, patent, and trade secret law. Archives

February 2021

Categories |

612.386.0565

Copyright 2021. Weaver Legal and Consulting LLC. | All rights reserved.

Website by RyTech, LLC

Copyright 2021. Weaver Legal and Consulting LLC. | All rights reserved.

Website by RyTech, LLC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed