The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit recently considered an entertaining case. Viacom, the owner of the wildly popular “SpongeBob SquarePants” television series, sought to prevent a third party from opening a restaurant under the name “The Krusty Krab.” Krabby Patties, anyone? As millions of people know, Viacom launched the “SpongeBob SquarePants” television series in 1999. Since that time, Viacom has expanded the “SpongeBob” concept into two feature films and a wide variety of licensed products. All of these ventures prominently feature The Krusty Krab fast food restaurant. Notably, prior to the lawsuit in question, Viacom had not sought to register The Krusty Krab as a trademark. In 2014, IJR Capital Investments decided to open seafood restaurants in California and Texas under the name The Krusty Krab. Subsequently, IJR filed a trademark application in the U.S. Trademark Office for THE KRUSTY KRAB. Upon learning of IJR’s trademark application and restaurant plans, Viacom sent a cease and desist letter in November 2015. IJR refused to cease use of The Krusty Krab, and Viacom subsequently filed a lawsuit in January 2016. A central legal question within the case was whether fictional elements of a television show can be protectable trademarks. More specifically, is The Krusty Krab a protectable trademark? As a threshold issue, an important question in the case was whether specific elements from within a television show - as opposed to the title of the show itself – receive trademark protection. In deciding this issue, the court looked to previous decisions from other courts that found protectable trademark rights in Conan (from “Conan the Barbarian”), the General Lee (from “The Dukes of Hazzard”), and the Daily Planet (from “Superman”). In line with these prior decisions, the court concluded fictional elements in entertainment entities can be protected as trademarks. Turning to the Viacom case, the salient question was whether The Krusty Krab mark, as used, will be recognized in itself as an indication of origin for the particular product or service. The mark must create a separate and distinct commercial impression to perform the trademark function of identifying the source. The court concluded that Viacom uses The Krusty Krab as a source identifier and therefore owns the mark. In support of its decision, the court reasoned that the Krusty Krab’s central role in the multibillion-dollar SpongeBob franchise, coupled with the consistent use of the mark on licensed products establishes ownership of the mark because of its immediate recognition as an identifier of Viacom as the source for goods and services. Since filing the lawsuit, Viacom has filed three trademark applications for “KRUSTY KRAB” for some diverse goods/services, such as plastic cake decorations, aquarium ornaments, and providing a website featuring general interest entertainment information related to television programs and cartoons for entertainment purposes.

0 Comments

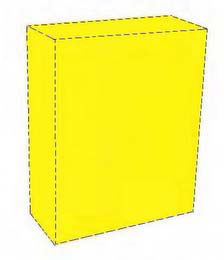

Effective June 1st, the U.S. Patent Office updated its fee schedule to reflect an increase in the search fee for international patent applications that designate the Japan Patent Office (JPO) as International Searching Authority. The search fee increased from $1,385 to $1,465. The current fee schedule for all International Searching Authorities is: For patent applicants, designating the USPTO as ISA provides the opportunity to qualify for reduced fees (small entity or micro entity). However, cost should be just one of the factors considered when deciding which ISA to designate for a patent application.

Many of my clients opt for a foreign patent office as ISA based upon their potential markets. Not only will the search be different in scope, but it may be more relevant if the subject technology primarily resides in a country outside the United States. The European Patent Office remains the most expensive option for ISA, while Australia, Singapore and Japan remain in an intermediate cluster. The choice of ISA could impact a patent applicant’s future prosecution, both within the United States and globally. Cost, value, potential markets, and technical relevance are important factors to consider when selecting an International Searching Authority. This month, Weaver Legal and Consulting is 5 years old! Weaver Legal was founded in 2013 based upon 16 years of intellectual property (IP) experience in both private and corporate practice. As a full-service intellectual property firm, Weaver Legal utilizes all areas of IP, including patent, trademark, trade secret and copyright to protect your valuable ideas. Here are some highlights of my practice: Global legal practice  Represent clients on 5 continents Representative patent technologies:  ● Medical devices ● Crosslinking agents for coating technologies ● Drug release coatings ● Implantable three-dimensional scaffolds ● Neural transfection technology ● Cell culture devices and coatings ● Scaffolds for electrically excitable cells ● Polymer coating compositions ● Composite technology – fabric & polymeric based ● Desiccant materials ● Fire suppression compositions Representative trademark industries:  ● Cell culture devices ● Polymer coating compositions ● Medical device coatings ● Chemical reagents ● Bakery services ● Café services ● Retail services ● Composite technologies ● Apparel ● Hormone therapy services ● Fire extinguishing compositions Community:  Included in the 2017 Wisconsin Access to Justice Commission Pro Bono Honor Society. Pro bono legal work includes: ● New local business start-ups ● New & existing nonprofit organizations in Wisconsin and Minnesota These first 5 years have brought much excitement and growth for Weaver Legal, and I can’t wait to see what the next 5 years bring. How can I help you? The US Trademark Office Wants to Make Electronic Filing Mandatory – Trademark Owners Take Note5/31/2018 Yesterday, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) published proposed amendments to the Rules of Practice in Trademark Cases. The proposed changes are significant for anyone who deals with the Trademark Office directly, particularly trademark owners who choose to work with the USPTO without an attorney. See the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking here. First, a little background When I began practicing law in a Minneapolis firm in the 1990s, we were still filing trademark applications and related documents on paper. Early in my career, I remember the USPTO introducing the Trademark Electronic Application System (TEAS), which allowed us to file trademark applications electronically. This was followed by the Trademark Status and Document Retrieval (TSDR) system, where we could check the status of our trademark cases and view electronic records within the Office. These developments have streamlined the trademark application process and allowed trademark owners to manage their marks efficiently and effectively. The USPTO continues to strive to make the trademark application, registration, and maintenance process efficient and cost-effective. According to the USPTO, over 99% of applications under §1 and §44 of the Trademark Act are currently filed electronically. However, only about 87% of these applications are processed electronically end-to-end. In a push to convert the entire process to an electronic system, the USPTO has proposed to amend its Rules of Practice to require electronic filing through application prosecution and post-registration. Proposed Rules The USPTO’s proposed Rules would make almost all communication with the Trademark Office electronic. Specifically, the proposed amendments would:

Under these new rules, trademark applicants and registrants would be required to not only file the original application electronically through TEAS, but also submit all future correspondence relating to their applications or registrations through TEAS. Such correspondence includes, for example:

Regarding item #3, the email address you provide to the Office will be the address where the Office sends all correspondence relating to your trademark. In my practice, I often communicate directly with Trademark Examining Attorneys to resolve minor issues over the phone and/or through email. This practice is highly efficient and allows me to obtain trademark registrations for my clients very quickly. The new Rules would allow trademark owners and attorneys to continue this type of practice. These proposed Rules are open for comment through July 30, 2018. Potential Risks of Electronic-Only Processing The proposed rules introduce risks for trademark owners who handle their applications and registrations themselves. Under the new rules, the USPTO would send all correspondence via email. If an email transmission fails because, for example, the user’s mailbox is full, the user provided an incorrect (or outdated) email address, or the email provider has a service outage, the USPTO will not attempt to contact the correspondent by other means. This places the burden of keeping on top of trademark status squarely on the trademark owner. If the USPTO sent you an email, but you did not receive it, you are not excused from knowing what was in that communication. The proposed rules do provide some very limited scenarios under which the Office would consider paper correspondence: specific foreign applicants (designated under a treaty), and specimens for scent, flavor, or other non-traditional trademarks. There is also a procedure to petition the Office to accept paper submissions. However, these exceptions and petition procedures are limited. Practice Tips In light of these proposed rules, trademark owners should take steps to prepare for the possibility of electronic-only procedures at the Office. Here are 5 tips to consider:

Regarding item #4, the USPTO’s policy has always been that service outages do not necessarily relieve you of your obligation to submit documents on time. So, for example, if you wait until the date a submission is due to the Office, and the electronic service unexpectedly goes out (for example, your Internet, or even the USPTO TEAS system), you are not excused from complying with the deadline. Many of my clients have heard my cautionary tales of trademark owners who waited until a deadline to provide me with filing documents, only to have either the Internet service or TEAS go down. You can easily avoid unnecessary costs and hassle by filing documents before the deadline. Is your business ready for electronic filing for all of your trademark matters? You may want to consult a trademark attorney to provide you with guidance. Perhaps it is time to engage an attorney to manage your trademarks for your company. In addition to experience handling matters before the USPTO, attorneys have docketing systems that monitor Trademark Office records and track deadlines. Your trademarks are valuable assets for your company. Make sure you take steps to protect those assets. Starting a new business is really exciting. You are ready to take your ideas and create something new. Congratulations! One of the very first things you need to do is secure your company name. This is the name that will represent you and your business. It will come to be synonymous with your goods or services in the minds of your customers. You will use it on your website, social media, business cards, marketing materials, your storefront, etc. The number one issue I have seen with my entrepreneurial clients is having to change their company name because they find out someone else is already using it. Having to change the name of your business after you have already started your marketing (and maybe even sales) is costly and time-consuming. And it can be confusing for your customers. Here’s how to efficiently invest some time upfront, so you choose and secure a company name that can stick: Develop a short list of 3-5 possible names. Brainstorm 3-5 possibilities and rank them, starting with your favorite. Do some searching. Type your candidate names into search engines like Google to see what turns up. Another useful place to search is the Secretary of State in your state, as well as the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Delete any candidates that are already out there, and brainstorm new names if you have to. Test your potential names with close friends and family. It can be useful to have people close to you take a look at your potential names and give you feedback. Be careful to only ask people you trust – I have had clients find out someone heard their name and “scooped” them by registering the name ahead of them. This is potentially illegal, but it would cost money to prove that. Contact an attorney. A trademark attorney with experience in searching can help you make sure there are no third party uses out there that could cause a problem for you. Tell them what searching you have already done, and what you have found. The attorney can supplement your search with their own resources (I personally have subscriptions to specialized search tools) and advise you whether any there are any possible issues. File early! Once you settle on a company name, start reserving that name right away.

For Minnesota: https://mblsportal.sos.state.mn.us/Business/Search For Wisconsin: https://www.wdfi.org/_resources/indexed/site/corporations/dfi-corp-1.pdf

Even if you are not ready to open the doors for your new venture, you should consider how to best protect your company name. Taking these steps early will give you peace of mind about your company name - and will save you headaches in the future. Earlier this week, a new Wisconsin law took effect that creates the benefit corporation. 2017 Wisconsin Act 77, which went into effect February 26th, creates and defines this new category of corporation.

In a nutshell, a benefit corporation is a for profit entity that seeks to achieve a public benefit. The benefit corporation thus marries profit and purpose. We all know what profits are. But what is a “public benefit?” The new Wisconsin law provides us with some illustrative examples, including:

The concept of benefit corporations has been evolving for the past two decades. State laws began codifying the corporate structure in 2010, when Maryland passed the first state law establishing this type of business entity. In less than 8 years, 34 states have followed suit, underscoring the importance of this trend. Some examples of benefit corporations include Ben & Jerry’s, Etsy and Patagonia. So, why would a company want to become a benefit corporation? One of the most important aspects of the Wisconsin statute is that it creates transparency and auditing mechanisms for companies who wish to hold themselves out to the public as a benefit corporation. Benefit corporations must file an annual benefit statement, which sets out the objectives the board of directors has established to promote public benefit, standards for measuring the corporation’s progress in meeting those objectives, and an assessment of the corporation’s success in meeting its objectives. Another key feature of Wisconsin’s benefit corporation law is that it provides liability protections for the corporation’s board of directors. Oftentimes, the board of directors will find some tension between meeting typical corporate objectives (profits for shareholders) and a public benefit. Wisconsin’s law recognizes that directors will consider both profits and public benefit when acting on behalf of the corporation. Already a corporation under Chapter 180 or 181 of Wisconsin Statutes? Not a problem. You can convert your company to a benefit corporation by following some simple steps. Starting up a new company? You may want to investigate whether the benefit corporation is the right structure for your company. There are many potential benefits of the benefit corporation structure. If you are seeking investment capital, potential investors may find your public objectives an attractive feature. Being able to market yourself as a benefit corporation can also solidify your brand identity as socially conscious and connected to your community and environment. Consumers increasingly look for ways their spending can benefit their communities. If your company has sincere interest in pursuing one or more public benefits, yet you also wish to make a profit, you may want to consider whether a benefit corporation is the right structure for you. Many of us have been enjoying the winter Olympics in PyeongChang. If your home is like mine, the television runs in the background every night, keeping us updated on our favorite athletes and their quest for medals.

Did you know that the U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) has intellectual property (IP) rights in many of the images, logos, words and phrases associated with the Olympic and Paralympic Games? In fact, the USOC is so serious about its IP that it has a webpage dedicated to its brand usage guidelines - https://www.teamusa.org/brand-usage-guidelines. When many people think about IP, they think about corporate profits and monopolies. However, the stated mission of the International Olympic Committee is to “not only ensure the celebration of the Olympic Games, but to also encourage the regular practice of sport by all people in society, regardless of sex, age, social background or economic status.”[1] So, why would the USOC claim exclusive rights to these images and logos, if the spirit of the Olympics is to contribute to building a peaceful and better world through sport? The answer is funding. The USOC oversees amateur athletics in the United States and is responsible for overseeing training, funding and sending Team USA to the Olympic and Paralympic Games every two years. Unlike other national Olympic committees around the world, the USOC does not receive government funding to support these activities. So, it seeks official corporate sponsors to fund its programs. In return for sponsoring the Olympic Games, an official sponsor can use USOC trademarks in its media and advertising. The Olympics generate a lot of excitement, as we cheer for Team USA, learn interesting facts about the athletes, and celebrate medal winners. There is much media hype before and during the actual Games. Advertising in connection with the Olympics is valuable, and the list of official sponsors includes many venerable global companies. You have probably spotted logos on athletes’ apparel and maybe memorized some of the commercials featuring official sponsors. The USOC has identified its valuable IP and controls who can and cannot use its trademarks, logos and other rights. If you want to use any of its trademarks, you must seek permission (and pay the appropriate fees) to the USOC. If the USOC did not tightly control who could use its trademarks, the value of sponsorship would be significantly reduced. This would ultimately diminish the ability of the USOC to raise money for Team USA. What are some of the USOC trademarks? Many of the logos and images are set forth on the brand usage guidelines website noted above, and include the Olympic rings in combination with the US Flag and other images and phrases from current and future host countries. In addition, the USOC owns trademarks on the following terms:

And many more. This is a great example of how an organization can identify, organize and utilize its IP rights (and in particular, trademark) to generate operational funds. What could your company take from this example? Author’s note: Weaver Legal and Consulting LLC has no official connection or sponsorship arrangement with the Olympics or the USOC. [1] https://www.olympic.org/the-ioc/promote-olympism A copyright is a bundle of rights in an original work of authorship. This is an important area of law because it deals with the right of an author or artist to receive credit (be acknowledged) for creating their work. It is a way of recognizing the creativity and effort that has gone into crafting a new work.

Copyright is an intricate area of law, which is grounded in our U.S. Constitution and codified in federal law. If you have questions about your copyright, it is best to contact an intellectual property attorney who has knowledge in this area. That being said, here are ten things you should know about copyright. 1. What does copyright protect? Copyright protects original works of authorship, including:

The work must contain at least a minimum amount of creativity in order to be protectable by copyright. 2. What is the “bundle of rights” copyright protects? The owner of a copyright has the exclusive right to:

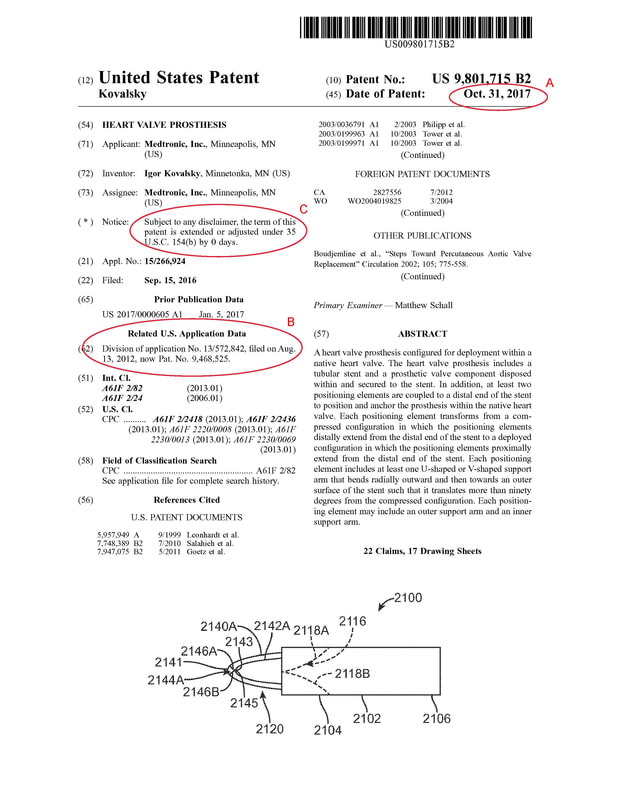

Copyright infringement occurs when any of these exclusive rights are violated. 3. Who owns a copyright? Copyright is owned by the author of the work – that is, the person who created it. 4. Can I find out if someone owns a copyright in a work? Your best starting place is to examine the work to locate a copyright notice. That notice should include the name of the owner. You can also look at the context of the work, to determine whether any clues may tell you who owns rights in the work. You can search records at the Copyright Office through its Copyright Catalog, which is found on their website, www.copyright.gov, under the “Resources” heading. The catalog includes works from 1978 to present. However, the Copyright Office cautions that searching records can often be complex and incomplete. Therefore, if you do not find owner information in the Copyright Office Catalog, this does not mean the work is not protected by copyright. 5. How is copyright different from a patent or trademark? Along with patent, trademark and trade secret, copyright recognizes and protects intangible products of the mind. These areas of law are commonly referred to as intellectual property. Generally speaking, copyright protects original works of authorship, while patents protect inventions, and trademarks protect words, phrases, symbols or designs that identify a source of goods or services of one party and distinguish them from those of others. All of these forms of protection can be used together to protect a company’s valuable intellectual property assets. 6. When does copyright protection begin? Copyright protection begins once your work is created and fixed in a tangible form. 7. Do I have to register my work with the Copyright Office to have protection? No. Generally speaking, copyright registration is voluntary. However, if you wish to bring a lawsuit for infringement of a U.S. work, you will need to register your copyright. Registration may also provide you with evidentiary benefits in court and may provide access to additional damages if your lawsuit is successful. 8. If I want to register my copyright, how can I do it? To register a copyright, you will need three things: (1) an application form, (2) a filing fee (either $35 or $55, depending upon the material you wish to register), and (3) a nonrefundable deposit of the work – a copy or copies of the work being registered and “deposited” with the Copyright Office. You can apply to register your work online or in paper. To begin either process, you will need to visit the Copyright Office website: www.copyright.gov. The online application can be found by clicking on electronic Copyright Office from the website. The paper application can be found under the Forms section on the website. 9. Can I copyright my website? Yes, original authorship appearing on a website may be protected by copyright. Some elements of a website that may be copyrightable include: text, photographs, illustrations, and other two-dimensional artwork, music, sound recordings, and videos or other audiovisual works. As a general rule, you should submit a separate application for each component work appearing on your website. 10. How long does a copyright last? As a general rule, for works created after January 1, 1978, copyright protection lasts for the life of the author plus an additional 70 years. If two or more authors created a work together, the term lasts for 70 years after the last surviving author’s death. The term of copyright will run through the end of the calendar year in which it expires. Bonus: Practice Tip. Use a copyright notice on all of your original work. This is an easy, inexpensive step you can take to put the public on notice that you claim rights in your work. A typical copyright notice will include the “circle R,” a date, a reservation notice, and the name of the owner. For example: © 2018 Weaver Legal and Consulting, LLC. All rights expressly reserved. The copyright notice will also give any person who would like to use your material a way to contact you. As an added bonus, this gives people a way to contact you for follow up questions and can lead to new connections. I hope this general information is helpful to you. If you would like to read more, the Copyright Office website has a wealth of information. I am also happy to answer questions or provide additional information.  Recent efforts by General Mills to assert rights in the color yellow in connection with its CHEERIOS® breakfast cereal boxes have brought the issue of how color can function as a trademark into focus once again. Since at least as early as the 1980’s, U.S. trademark law has recognized that color can function as a trademark and is thus eligible for trademark protection. In its 1995 Qualitex decision, the Supreme Court definitively agreed, concluding that “sometimes, a color will meet ordinary legal trademark requirements. And, when it does so, no special legal rule prevents color alone from serving as a trademark.” As with all legal statements, the key is in the word “sometimes.” How Can Color Become a Trademark? Acquiring trademark rights in a color is not an easy task. A company must show that the color has become distinctive of its goods in commerce, and that the color does not serve any other significant function. Here are some well-known examples of companies who have successfully established trademark rights in a color: Owens-Corning Pink, Qualitex green-gold, Tiffany Blue, Barbie Pink, Wiffle Ball Bat Yellow, UPS Brown, 3M Canary Yellow, Target Red, Coca Cola Red, Christian Louboutin (red outsoles on shoes), and The Home Depot Orange. For a color to function as a trademark, customers must come to treat a particular color on a product or its packaging as signifying a brand. Taking Owens-Corning Pink as an example, the pink coloring of its insulating material seems unusual in context, and the particular hue has no other significant function. That color has come to identify and distinguish the insulation products – to indicate their source. In this instance, the color has acquired “secondary meaning,” where, in the minds of the public, the primary significance of the color is to identify the source of the product rather than the product itself. Limits to Color as a Trademark Against this backdrop, General Mills recently attempted to register the color yellow on packages of “toroidal” (ring or doughnut-shaped) oat-based breakfast cereal, the company’s CHEERIOS® cereal. The trademark application looked like this: General Mills described their trademark as consisting “of the color yellow appearing as the predominant uniform background color on product packaging for the goods. The dotted outline of the packaging shows the position of the mark and is not claimed as part of the mark.” The U.S. Trademark Office refused the trademark application, and General Mills appealed to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB). The TTAB agreed with the USPTO and rejected General Mills’ bid to register yellow for its CHEERIOS® cereal. In deciding the case, the Board conceded that “by their nature color marks carry a difficult burden in demonstrating distinctiveness and trademark character.” The record showed that General Mills had begun using the color yellow on its CHEERIOS® cereal boxes at least as early as 1944. The company introduced evidence that it had expended over $1 billion in marketing in a single decade, and that sales of CHEERIOS® cereal exceeded $4 billion in that same period (1995 to 2015). In looking at General Mills’ trademark application, the Board was influenced by the existence of several other companies who use yellow colored cereal packaging (boxes and bags) for similarly-shaped, oat-based cereals, including some of General Mills’ competitors. The Board concluded, “The presence of products of this type in the marketplace interferes with the development among relevant customers of a perception that the color yellow on packaging indicates that Applicant is the source of the goods (or that there is any single source of such goods)." Think about the cereal aisle in your local grocery store. When you turn down this aisle, you are often confronted with a rainbow of brightly colored packaging, for a large number of different cereals. Several of these boxes are yellow. The Board found that customers are accustomed to seeing numerous brands from different sources offered in yellow packaging and are likely to view yellow packaging simply as eye-catching ornamentation customarily used for the packaging of breakfast cereals generally. The Board also looked at the industry practice of ornamenting breakfast cereal boxes with bold graphic designs and prominent word marks (in addition to bright background colors). Looking at General Mills’ cereal packaging generally, the Board found that customers do not perceive the color yellow alone indicate the source of General Mills’ breakfast cereal. The CHEERIOS® “yellow box” case demonstrates the difficulties in protecting trademark rights in a color per se. This case presents a refinement in color trademark law, as well as guidance for companies interested in non-traditional trademark protection for their valuable brands. A patent is issued in the name of the United States under the seal of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). A patent confers “the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United States or importing the invention into the United States” and its territories and possessions for a period of time. So, how long does a patent last? On the date a patent issues, the “right to exclude” comes into force. So, how long can a patent owner exclude others from the above activities, or in patent parlance, what is the “patent term?” To determine the “life” of a patent, you must start with the earliest filing date of the patent application in the United States. Generally speaking, a patent term is 20 years from that date. In order to keep that patent in force, the patent owner must pay maintenance fees at three specific time periods during the patent term. Four important aspects of a patent term thus include: (1) what is the issue date of the patent, (2) when was the application first filed in the US, (3) has the USPTO adjusted the patent term, and (4) when are maintenance fees due? It is best to consult a patent attorney or agent to determine the actual expiration date of a patent, but you can begin to calculate the expiration date by looking at the front page of the patent of interest. For example, in the patent below, you can see (A) the issue date of the patent (the date from which the patent is in force), (B) the earliest date the application was filed in the United States, and (C) the patent term adjustment: In this Example, the patent rights are in force on October 31, 2017 (A). It was first filed in the United States on August 13, 2012 (B), and it did not receive any patent term adjustment (C). Now to the calculation: 20 years from (B) is August 13, 2032 + zero (0) days of patent term adjustment = an expiration date of August 13, 2032. The patent owner can enforce the patent for the period of October 31, 2017 to August 13, 2032, so long as they pay maintenance fees. Although it is best to verify items (B) and (C) through the USPTO Patent Application Information Retrieval (PAIR) system, this can give you a starting place for determining the patent term. You can access Public PAIR here: https://portal.uspto.gov/pair/PublicPair Maintaining the Patent Once the patent is issued, it must be maintained by paying maintenance fees to the USPTO. The USPTO established three 6-month time periods during the patent term when maintenance fees are due: (1) at 3 to 3.5 years; (2) at 7 to 7.5 years; and (3) at 11 to 11.5 years. These dates are measured from the Date of Patent, (A) in the example above. If a maintenance fee is not paid by the due date, there is a grace period of 6 additional months after the deadline, during which the fee can be paid (with a surcharge). Information about paying maintenance fees can be found at: https://www.uspto.gov/patents-maintaining-patent/maintain-your-patent. To see specific maintenance fee deadlines and whether a patent owner has paid them, select “View maintenance fee information” from this webpage. After a patent expires, either by running through its 20-year term, or because the patent owner failed to pay a maintenance fee, the public is free to use the invention claimed in that patent. Note, however, that this right is subject to any other patents that may exist in the particular field. Patent terms are as individual as the technology they describe. Although this article provides some guidelines for understanding how long a patent can be enforced, additional technical considerations such as terminal disclaimers, have not been covered. It is best to consult with a patent attorney or agent to determine the specific patent term and implications of a specific patent. Questions? Feel free to contact me. |

AuthorKarrie Weaver practices intellectual property, trademark, patent, and trade secret law. Archives

February 2021

Categories |

612.386.0565

Copyright 2021. Weaver Legal and Consulting LLC. | All rights reserved.

Website by RyTech, LLC

Copyright 2021. Weaver Legal and Consulting LLC. | All rights reserved.

Website by RyTech, LLC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed